Feliciano Giustino Uses Quantum Mechanics to Create New Materials

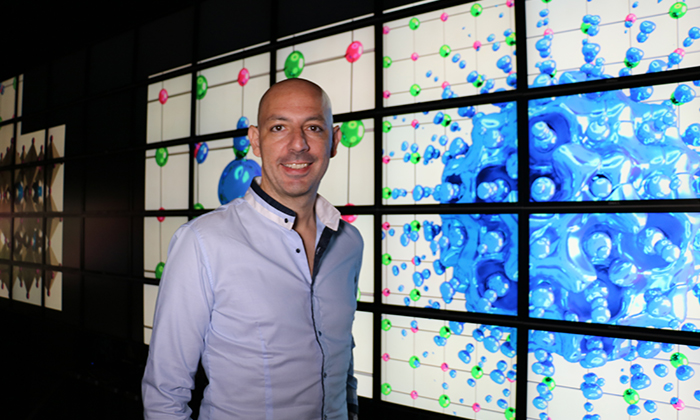

Feliciano Giustino, Moncrief Chair at the University of Texas' Oden Institute. Courtesy of Dr. Giustino

Feliciano Giustino recently joined the University of Texas at Austin faculty in the Department of Physics and is a Moncrief Chair in the Oden Institute for Computational Engineering and Sciences, where he will direct the Center for Quantum Materials Engineering. He was previously a professor in the Department of Materials at Oxford University.

We sat down with Giustino to discuss his current research focus, hopes for the future of his field and why he chose Texas.

What first sparked your interest in physics?

There's actually a very famous movie in Italian cinema about the Via Panisperna boys, which describes the team of Enrico Fermi discovering radioactivity induced by slow neutrons. Essentially the movie is about a team of young people, who were all very good at physics, having fun and making discoveries that would later revolutionize science. Most kids who studied physics in Italy have seen the movie. I was inspired, and so I decided to study nuclear engineering.

How did you pivot from nuclear engineering to the theoretical work you're doing now?

After studying nuclear engineering in Italy, there was an opportunity to work at CERN. There I realized that I was not that interested in experiments, and I liked theory better. So, I looked for opportunities where somebody would take students to study the quantum theory of solids—which examines how various properties of solid materials arise from quantum mechanics—and that basically was the beginning of my PhD in computational physics.

You've studied in Italy, Switzerland, California, England and New York. Of all the places in the world this has taken you, why come to Texas?

I think there is a real opportunity to make something big here in Texas that would not be possible elsewhere. And one can clearly see the ambition of everyone here, and UT's ambition to become one of the leading universities in the world. I think it's exciting, and I want to be a part of it.

And what drew you to the Oden Institute in particular?

This institute recognizes the important role of computation as the third leg of science, beside theory and experimentation. And there is a lot of emphasis here on how important it is to develop new, more powerful computational methods and combine them with the best computers in the world.

There is really an advantage in using supercomputers to study materials …These techniques are getting extremely precise. We're at the point where these calculations are predictive in the sense that we can truly predict what will happen before you do the experiment.

What do you plan to study?

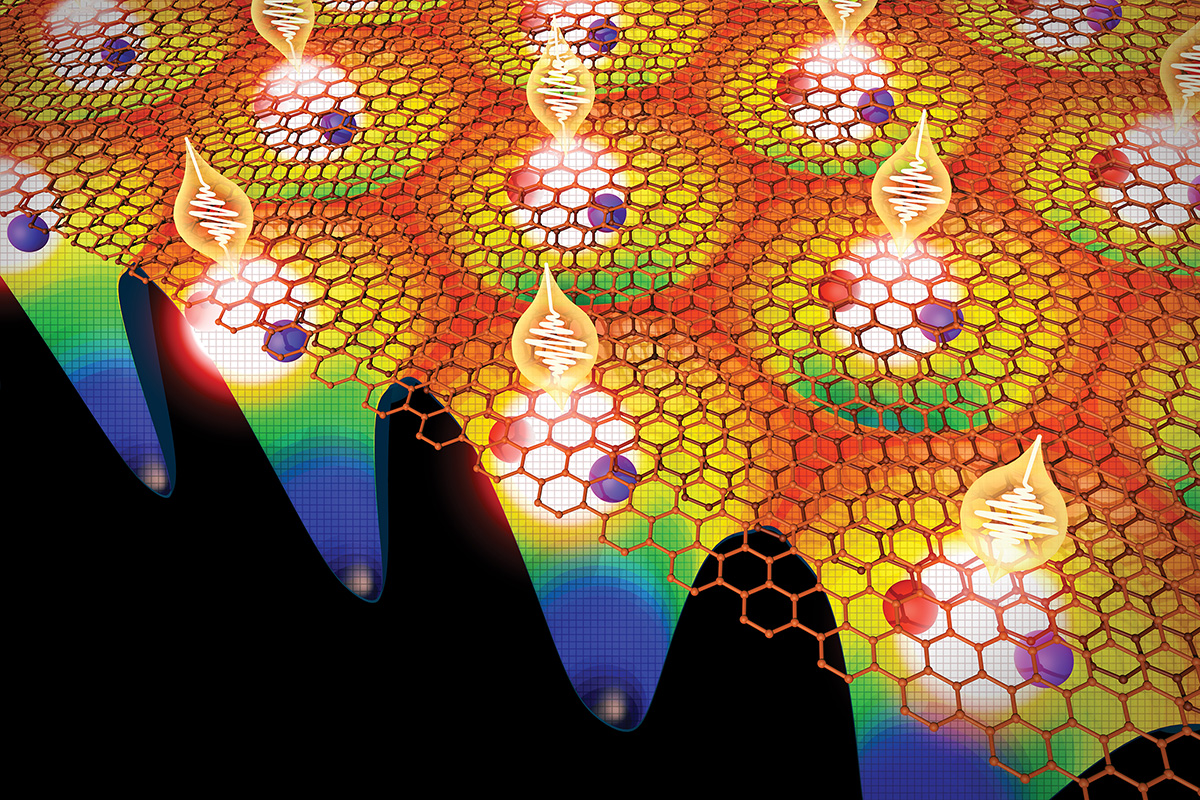

We're starting a new center, of which I'm the director, called the Center for Quantum Materials Engineering. The title simply means that we use quantum mechanics to engineer actual materials – not just find out their properties or understand them, but actually make new materials with tailored functionality.

If we can expand the range of properties that we can predict, these computational techniques will become extremely powerful. Hopefully in ten years, the number of properties we can cover will increase, and there will be a recognition from the experimental community that these tools are essential to discovery.

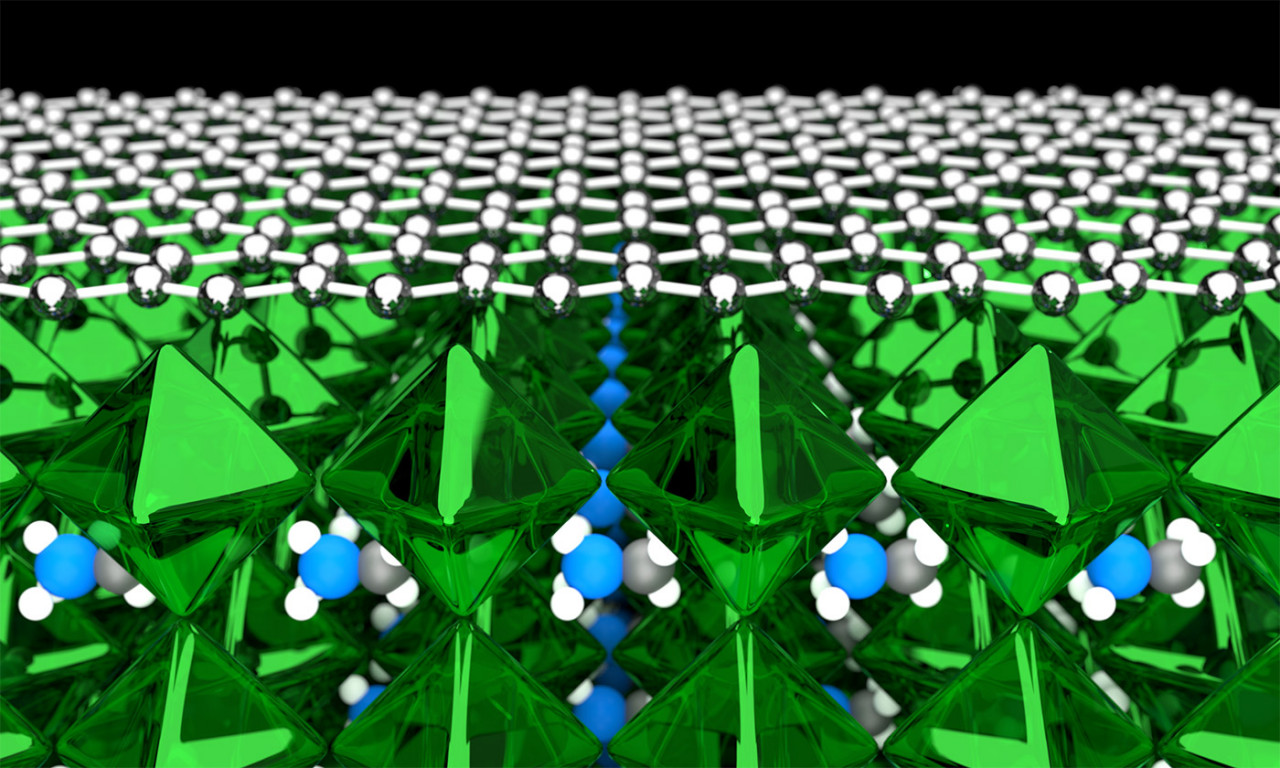

Atomic-scale model of the interface between graphene and a hybrid organic-inorganic perovskite for photovoltaics. Credit George Volonakis.

What kinds of materials will you focus on?

We study materials that could have applications or already have applications in energy, electronics and optoelectronics. For example, in the case of energy, we study materials that are used, or could be used in solar cells. We also study interesting materials that could make faster transistors or a transistor that uses less power.

With solar cells, we are interested in finding materials that absorb light and give as much electricity as possible in return. In principle, with an ideal material, we could extract 33 percent of solar energy. But, in practice, it doesn't work like that. Real, in-use silicon panels absorb about 20 percent. So, if one could find new materials, that for each photon, give you the theoretical maximum of electricity, it would be a revolution in terms of deploying very cheap solar panels everywhere.

What do you think of Austin so far?

One thing that is amazing is that it's sunny - which probably, to Texans, is obvious. But coming over from teaching in England, and being Italian, it's something that I appreciate.

Another pleasant surprise when I arrived that I was not expecting at all – I mean, everything is fantastic – there is an outdoor pool 1,000 feet from the office. I can go there, and I have my own lane, which has never happened in my life. Everywhere else you share the lane with three, four or five people. And here I have my own lane. Anytime I want. Outdoors. It's amazing.